Back to the Terminus project page.

May 10, 2011

The First Version of Terminus in Java

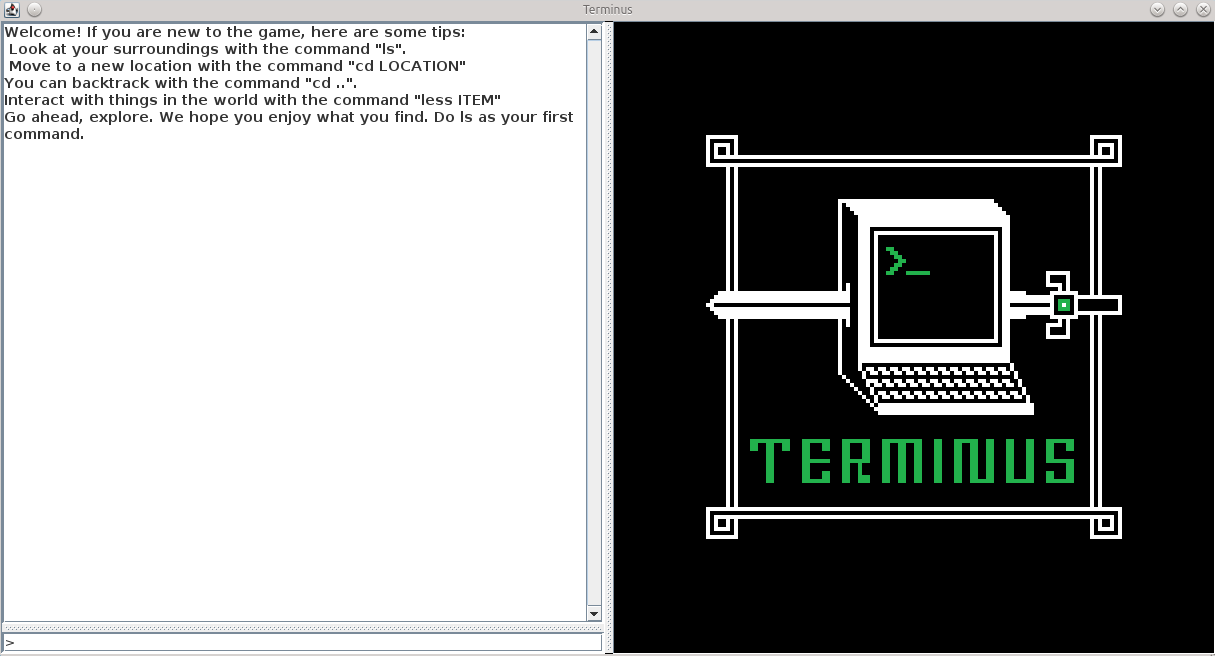

A first attempt was made in Java. It was pretty decent for a final project for a non-coding class. And it had sweet graphics.

Before you code: design!

The name of your game can make or break your success. Fortunately, Terminus sounds both sufficiently cool and sufficiently related to the word “terminal” that our job in that respect was done. The medium was also a no-brainer: the ideal metaphor is no metaphor at all. For us, because we were teaching terminal commands, it made the most sense for Terminus to be a computer game.

Before starting full-force on the development of the game, factors like the audience, basic mechanics, plot lines, and outstanding features need to be fleshed out to avoid unpleasantness later on.

Know the problem

We identified a few main barriers to learning terminal commands that we tried to overcome with game design and aesthetic choices:

- The terminal is ugly

- Documentation is convoluted, hard to find, and sparse

- The terminal is unforgiveable - if you mess up there is no “CTRL-Z”

- The immediate benefit of learning terminal commands is not obvious

The choices in mechanics and aesthetics attempt to battle (and in some cases mockingly mimic) these barriers.

Know the Audience

Our target audience was high school and early college students. These were people who have use for knowing terminal commands, or are likely to be deciding whether they “get” or “don’t get” computers. We wanted to capture and engage the population that would benefit from learning the terminal - either to advance their chosen academic track or to move them towards a technical education.

On one hand, this audience was an easy one, since we knew them well: we were in the same age group. On the other hand, this audience is a fickle one, hard to please and easily distracted. And yet another problem was that we did not exactly fall within our target audience, since most of us were already familiar with using the terminal. We anticipated problems later on for testing, but went ahead with the design process.

Game design: mechanics and play

A text-based adventure could only be successful if the gameplay, plot, and activities are engaging enough for the user. Our first big challenge was to create a storyline around the various terminal commands that was engaging enough for our target audience.

We settled on a basic gameplay that drew analogies between terminal concepts and fantastical experiences:

| computer | abstraction |

|---|---|

| file system | a series of rooms |

| terminal commands | spells |

| the cursor | your position |

And instead of commands like “go north”, we used parallels from the computing world to explain the new “spells”:

| command | abstraction |

|---|---|

| cd | “change direction” |

| ls | “look at your surroundings” |

| grep | a cute sidekick elf |

A huge benefit of the game being themed around magic is that any discrepancies with reality are merely brushed into the voodoo pile. The abstraction of a “spell” alludes to an underlying respect for the systems that you deal with when interacting with the terminal - it sets up the learner to expect to not understand everything at face value.

The game starts immediately with role play: you are a wizard in training, learning the spells of the great masters. You are told you are on a quest to find the sudo password, needing to enlist the help of grep your elf friend. As you interact with the environment, move through the world, and reach the end of the first level, you are given a series of tasks that force practice of basic commands like cd, ls, less, and mv. We identified these four commands has the most important to teach initially, based on merely our own experience. At first our design of the world, challenges, and tasks included practice of an ambitious set of commands, but time constraints forced us to pick a few to focus on. When moving forward, more thought and data gathering needs to be placed on which commands to introduce in order.

The environment itself was designed to be completely safe - you cannot execute arbitrary commands, and there is no possibility in harming the game itself with any mistakes. Unlike a real terminal, Terminus will forgive the user for their mistakes.

Game design: aesthetic

Lastly, we decided that the game would benefit from pictures that added to the allure of the game. Retro-pixel-art graphics would add to the gamification, bringing in silly pictures to reward the user when they typed correct commands.

The aesthetic was clean and simple: terminal on the left, rewarding picture on the right.

Java is the chosen one

I was nearing the end of my sophomore year at MIT when the Terminus project started. At that point, I was not yet a declared computer science major. I had taken 6.01, MIT’s introductory computer science class taught in very basic python, but the language I was most familiar with was Java. I had taken it in high school just 2-3 years before, and was taking 6.005, MIT’s software development class taught in Java, that semester.

11.127 was not a computer science class (by all MIT standards it was “a humanities class”) and therefore deserved the best ratio of excellence to effort. Out of our group of five, it was decided that Shawn and I were going to be the main coders. Because I was less experienced, we chose Java (my then-comfort language) as our language of choice - it would be easiest to code with the least amount of effort.

Absolutely no thought was given to the distribution of the game: we were going for pure ease of finishing. That’s how our first version of Terminus ended up as a Java program.

Back in the day before Github became cool, our code repository was hosted on MIT servers as a password-protected SVN repository. I have since uploaded the (decompiled Java) code to Github, but have lost all SVN commits and tags because of coding inexperience.

Graphics

Emma was excited about trying graphic design, so she took on the role of lead designer, making all the retro-90s-pixel-graphics for the first Java version of Terminus.

Lessons learned

The main takeaway from this design process was that no aspect of the design can be overlooked. We brainstormed and designed the gameplay and aesthetic, but neglected to think about the use case of a deployed version of the game: as a Java app, there is a high barrier to using the game in the first place. We should have approached building this game as a web application from the start. The technical challenges of building the application in Java (and with a time crunch of a final project deadline) were the challenges of novice coders building a system - version control, namespace variables, adequate commenting, and code system design were all issues we ran into that could have been improved for the next time.

Moving forward, don’t make Java apps if you want to have your products delivered, and make sure to use git rather than SVN.

In conclusion, the first version of Terminus as a Java application made a beautiful final project for 11.127/CMS.590.

All Posts about Terminus

2013 March 15 -- Education Designathon and iCampus Prize

2011 May 10 -- The First Version of Terminus in Java

2011 April 15 -- Gamification and a Linux Learning Game